With a century of history that has seen Mazda turn itself from a manufacturer of cork products to a successful independent global automotive company, Mazda’s story has always had engineering innovation at its heart and Mazda has never been afraid to highlight the capabilities of that engineering in the fierce world of motorsport competition.

By demonstrating its products in the public eye, putting them to the test against rival manufacturers on the racetrack and rally stage, Mazda validated its technology, marketed its cars across the globe and inspired countless privateers to compete in their own Mazdas at all levels of motorsport. This never stop challenging approach has seen Mazda compete from the very earliest stages of the company.

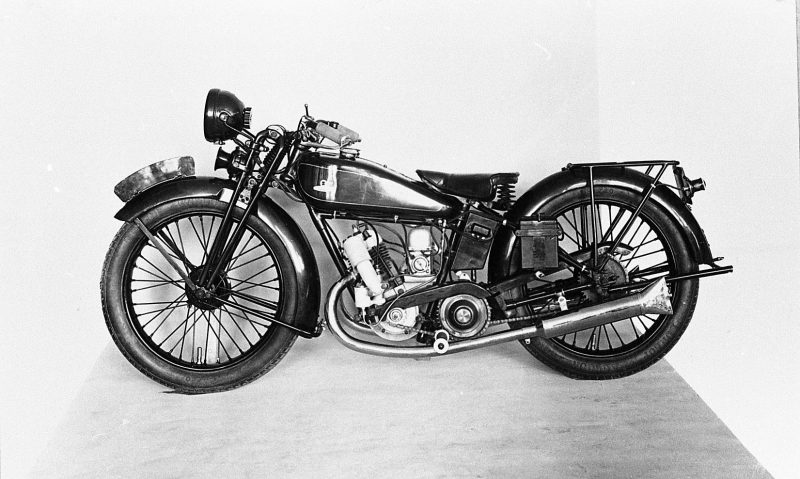

When industrialist Jujiro Matsuda took charge of Toyo Cork Kogyo Co., Ltd in 1921 and transformed the business first into a machine tool producer he spotted an opportunity to promote his evolving company. Motorcycle racing was popular in Japan in the late 1920s but most of the bikes were imported or assembled from imported parts. Toyo Kogyo, as Mazda was then known, wanted to build a domestic Japanese bike and began development of a prototype in 1929. A 250cc 2-stroke prototype motorbike was revealed in October 1930 and to everyone’s surprise it won its first race beating a British-made Ariel, which was one of the most-respected and fastest bikes of the time.

Toyo Kogyo went on to produce 30 more motorcycles in 1930, but commercially Matsuda took the decision to instead focus attention on developing the practical Mazda Go three-wheeler, setting the company on the road to success in automobiles rather than motorbikes, and leaving Mazda’s flirtation with motorbikes as a small snippet in the 100-year story of Mazda, but one that started with victory in motorsport.

However, this approach of using motorsport to promote the company and its new products was revisited three decades later as Mazda expanded to sell cars across the globe. Just seven years after the launch of its first car, the tiny R360 Coupe – Mazda revealed the stunning rotary powered Mazda Cosmo Sport. So, what better way to show the world this unheard-of Japanese sports car than to head to Europe and the hugely competitive world of European racing. And for this first foray into international motorsport in 1968 the company didn’t choose the easy option, instead they opted to test the endurance and reliability of the Cosmo’s rotary engine in the grueling Marathon de la Route – a mind-boggling 84-hour race around the fearsome 28km Nurburgring circuit.

While one car crashed out of the race, the surviving Cosmo finished fourth, beaten only by a pair of Porsche 911s and a Lancia Fulvia – considered at the time to be two of the finest sports cars in Europe. Mazda, the rotary engine and the stunning Cosmo had made their mark.

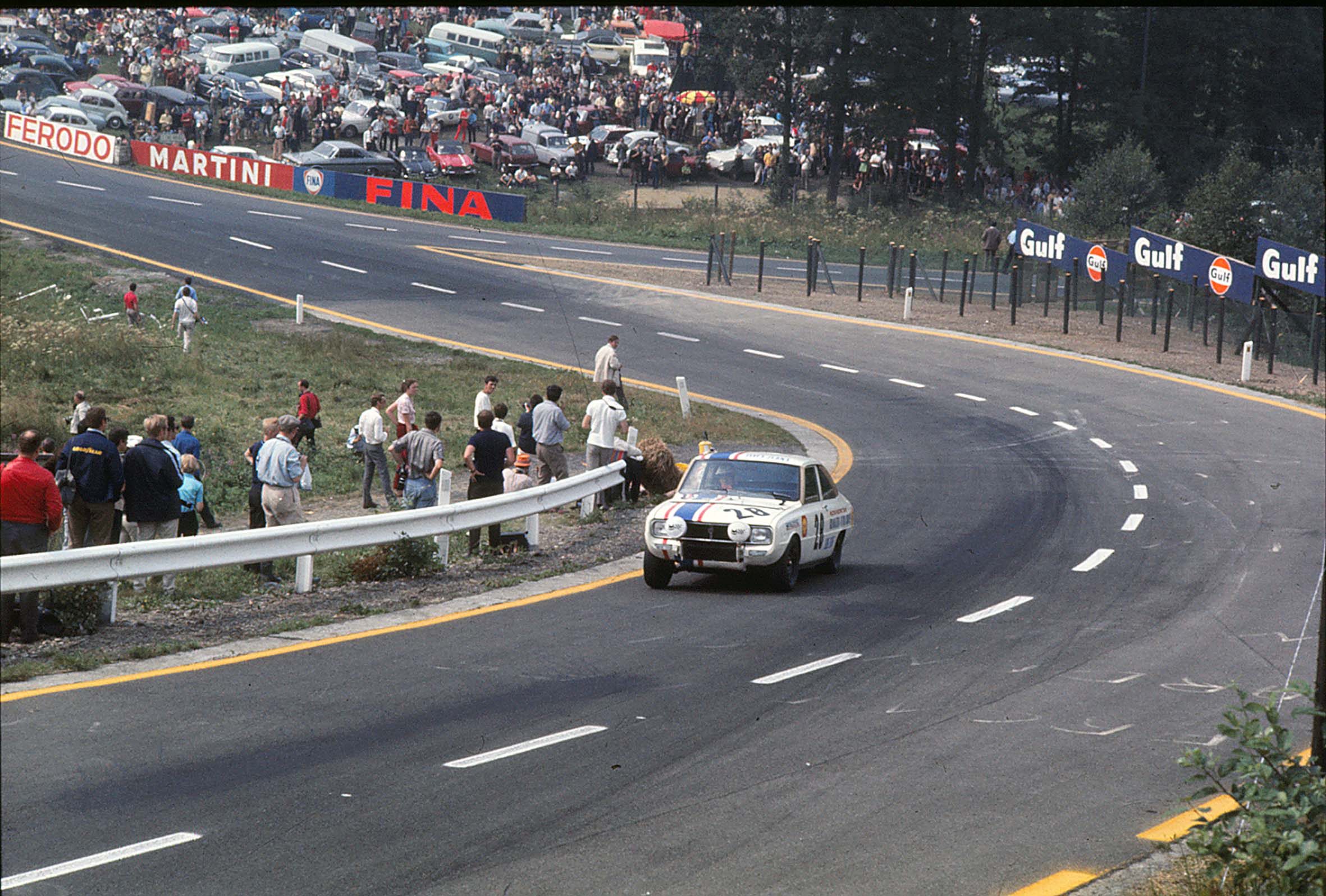

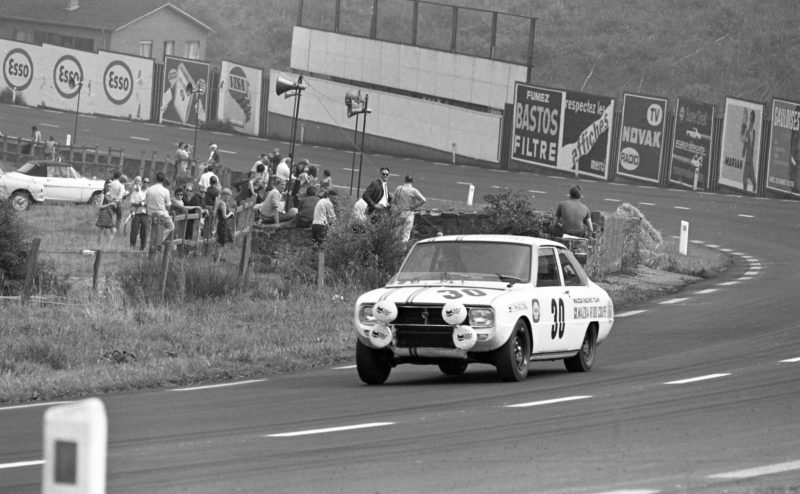

After success in the 1968 Marathon de la Route, in 1969 Mazda entered the Spa 24 Hour race with three Mazda R100 coupes. The R100’s twin-rotor engine produced 200bhp at 9,000rpm, while the unsilenced noise of the rotary engine left European fans in no doubt about the unique engine under the bonnet. Held on the ultra-fast original 14km Spa Francorchamps circuit this race tragically claimed the life of Mazda driver Leon Dernier, yet the Mazda team bravely continued to race.

Against competition from BMW, Lancia, NSU, Gordini, Mini, Alfa Romeo and Porsche, the remaining Mazda R100s finished fifth and sixth, behind four Porsche 911s. The little rotary powered coupes had proved their speed and reliability in one of Europe’s toughest races, while repeating the success of the Cosmo the year before, a R100 finished fifth in the 1969 Marathon de la Route.

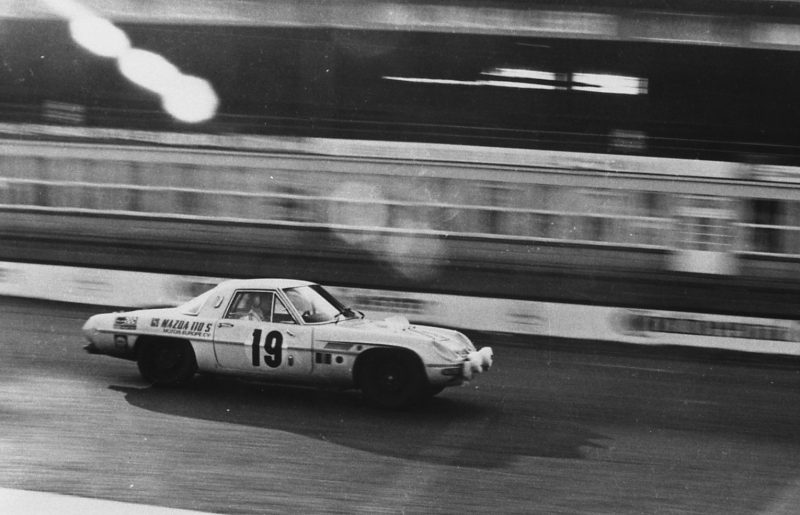

Building on these successes abroad, Mazda focused on racing at home in Japan – taking on the Nissan Skyline in domestic racing with the new RX-3 coupe. In the 1972 Fuji Grand Prix race for touring cars the RX-3s took a historic 1-2-3 finish as the battle for supremacy with Nissan reached a new level of intensity. The RX-3 also became a popular and successful race car around the world – competing in the USA, Europe and Australia.

Yet arguably the car that really put Mazda amongst the sports car greats was the Mazda RX-7. Across all three generations this Mazda icon took part in racing and rallying in a huge myriad of specifications in the hands of both the factory and privateer entrants. The Mazda RX-7 was used for Mazda’s first factory entry at Le Mans 24 Hours, but it was overall victory at the 1981 Spa 24 Hours – the first for a Japanese brand – that really put the RX-7 on the map. Alongside winning the British Touring Car Championship in 1980 and 1981, these victories for the British TWR team firmly established the RX-7 in the UK.

The RX-7 was also making its mark on the other side of the Atlantic where it enjoyed consistent success. Competing in the GTU class for cars with engines smaller than 2.5-litres it won the 24 Hours of Daytona at its first attempt in 1979. It then took the GTU championship for seven years on the trot. From 1982 it also lifted the GTO class (for cars with engines bigger than 2.5-litres) for 10 consecutive seasons. And while the class structures might have changed, the RX-7’s success remains undiminished: it has won more IMSA races than any other model in history.

Although its track exploits are well documented, the RX-7’s rallying achievements are less well known. On February 1, 1984, the RX-7 was homologated for the Group B category of rallying. The Group B RX-7 programme was created by Mazda Rally Team Europe, an operation set up by German rally driver Achim Warmbold and based in Belgium. Unlike other Group B cars which were four-wheel drive, the RX-7 was rear-wheel drive, nonetheless it recorded some successes, winning the 1984 Polish round of the European Rally Championship. Possibly a more notable success was its third place on the 1985 World Rally Championship Acropolis event in the hands of Ingvar Carlsson. However, when Group B rallying was banned at the end of 1986, the Mazda RX-7 was remembered fondly by rally fans for its flame-spitting rotary engine and the spectacular sideways technique demanded by its rear-wheel drive set-up.

For all the brand fame achieved by the motorsport activities of the Cosmo, R100, RX-3 and RX-7 coupes, it’s Mazda’s association with the world’s most famous race: the 24 Hours of Le Mans – that stands above all else.

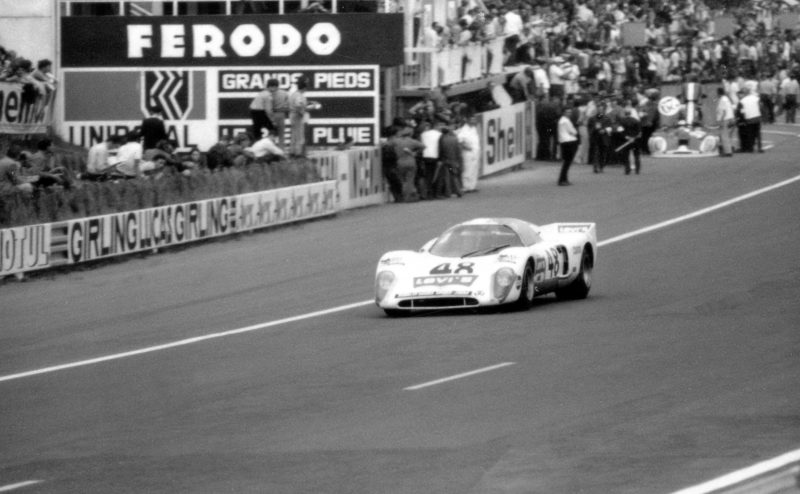

The first toe-in-the-water look at Le Mans came in 1970 when with a Mazda 10A rotary engine installed into a British Chevron chassis, Belgian outfit Team Levi’s International became the first team to compete at Le Mans with a Mazda engine. Sadly, the Chevron-Mazda retired after just 19 laps, but 1970 marked the beginning of Mazda’s long association with Le Mans. In both 1973 and 1974, a Japanese Sigma prototype was powered by a 12A rotary engine, while in 1975 a plucky French privateer team took part in an RX-3. The RX-7 made its debut at Le Mans in 1979 and in 1981 a pair of RX-7s were entered under the Mazdaspeed name, these streamlined RX-7s featured more powerful 300bhp twin rotor 13B engines.

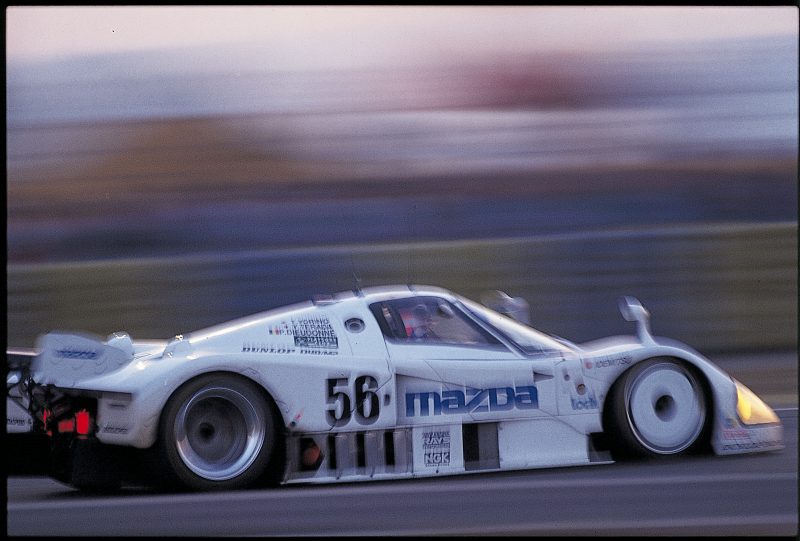

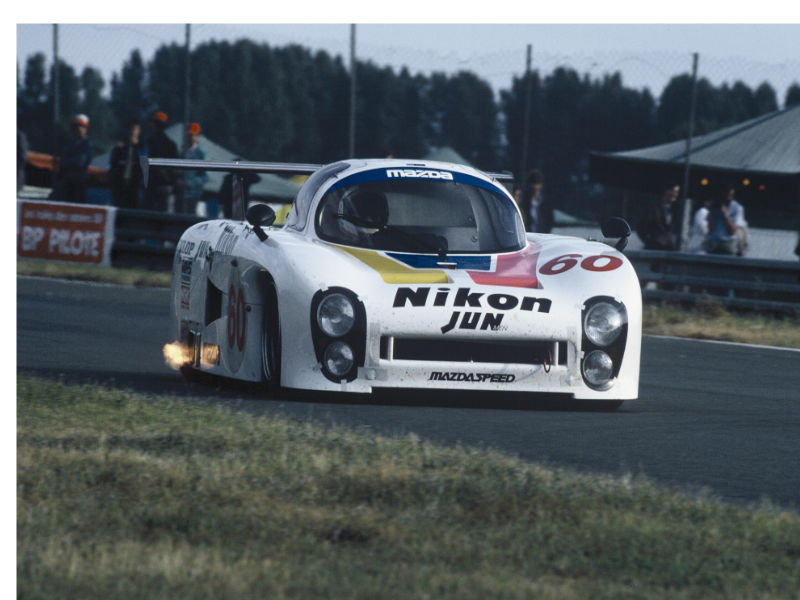

After another RX-7 entry in 1982, 1983 saw the factory Mazdaspeed team move into the prototype ranks with the diminutive Mazda 717C. Built for the 1983 Group C regulations and entered in the smaller Group C Junior class, the 717C was powered by twin-rotor engine and had an aluminum monocoque chassis. Its low drag bodywork and enveloped rear wheels were designed to ensure the highest possible speed along the famous Mulsanne straight and the slippery 717C had a drag coefficient of just 0.27cd. However, with very little downforce and a short wheelbase – the little Mazda was a handful for the drivers, but its speed and endurance resulted in a 12th place finish overall and the Group C Junior win for Japanese drivers Takashi Yorino, Yojiro Terada and Yoshimi Katayama. In fact, as a mark of Mazda’s reliability – the only other finisher in the Group C Junior class was the second 717C of British drivers Steve Soper, James Weaver and Jeff Allam, who took the flag in 18th overall.

In 1984 Mazdaspeed entered the renamed Group C2 class with a pair of Mazda 727Cs, an evolution of the previous year’s winning 717C, it used the same Mooncraft built chassis and twin-rotor 13B engine. However, Mazda’s attack was bolstered by a pair of sleek Lola T-616s entered by American Jim Busby. Powered by the same 13B rotary engine as the factory cars, the British built Lolas were shod with experimental BFGoodrich radial road tyres. At times the crowd were treated to the sight and sound of a quartet of rotary powered cars running together and all four Mazdas made the chequered flag – once again proving the durability of the twin-rotor engine. With Americans John O’Steen and John Morton joined by Mazda factory star Yoshimi Katayama, the number 68 Lola-Mazda crossed the line in 10th place overall and took C2 class victory. Even better, the sister Lola-Mazda took third in C2, with the leading 717C fourth in class.

Mazda’s tally of class victories at Le Mans continued during the late 1980s where Mazda scored a further three class victories: in 1987 the Mazda 757 of David Kennedy, Pierre Dieudonne and Mark Galvin won the GTP class and finished seventh overall, while the Mazda 757 took home another GTP trophy in 1988 with a 15th place finish for Yojiro Terada, David Kennedy and Pierre Dieudonne. Powered by a new three-rotor engine, the Mazda 757 was the first Mazda prototype chassis designed by Englishman Nigel Stroud, but it was only a stepping stone to the even faster and more powerful four-rotor Mazda 767, which made its debut alongside the 757 in the 1988 Le Mans 24 Hours.

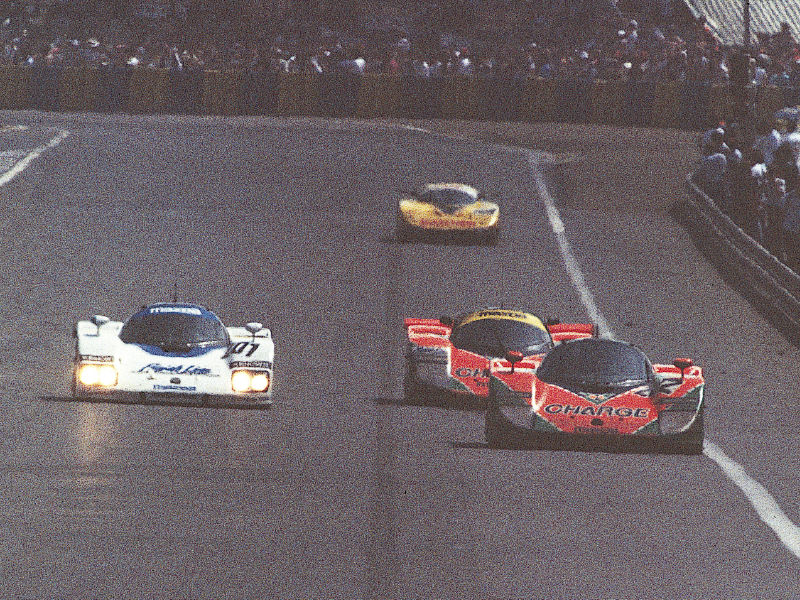

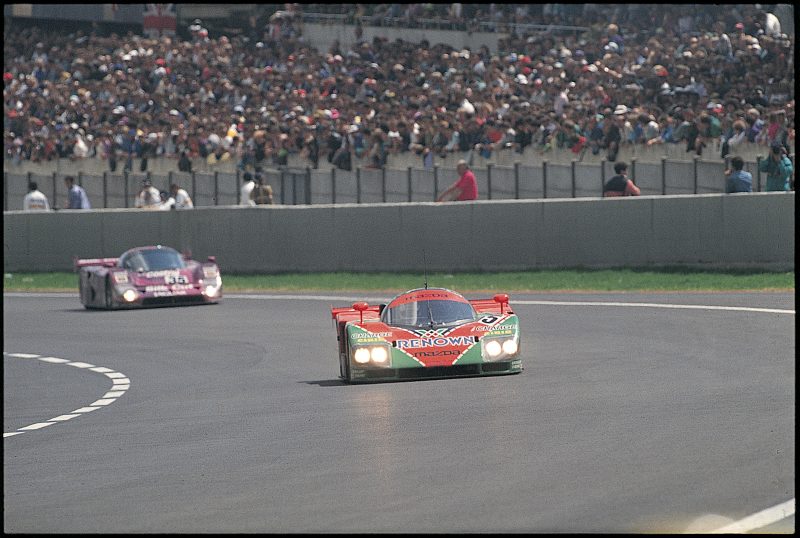

In 1989 its replacement the 767B took GTP class victory with a seventh-place overall finish, yet for all the class titles, Mazda’s real aim was to win the world’s most famous race outright and in 1991 that dream became a reality. The pinnacle of Mazda’s motorsport achievement and the ultimate validation of Mazda’s rotary engine technology that had been the cornerstone of Mazda’s Defy Convention approach to motorsport since 1968, the victory for Volker Weidler, Johnny Herbert and Bertrand Gachot in the Mazda 787B on the 23rd June 1991 was the first victory for a Japanese brand and in the world’s most famous race.

And it wasn’t just the rotary engine that pushed the technological boundaries, the Mazda 787B was the first car to win Le Mans with carbon brakes and a carbon clutch, plus it was the first Mazda racer to feature telemetry. Immediately retired from competition and placed in the Mazda Museum, 787B chassis 002 is today a fully working reminder of how Mazda’s Challenger Spirit led to victory at the world’s most famous race.

With rotary engines banned at the end of 1991, Mazda made one final factory appearance at Le Mans in 1992 with the radical Mazda MXR-01. Based on the previous seasons Jaguar XJR-14 chassis, the British firms’ withdrawal from sportscar racing, allowed Mazda to adapt this advanced Ross Brawn designed prototype and fit a Mazda badged V10 Judd engine. Famed for its incredible grip and downforce, just five examples where built, but sadly the collapse of the World Sportscar Championship at the end of 1992 spelt the end of Mazda’s world level sports car programme and denied the MXR-01 the chance of success. In America the Mazda RX-792P prototype used the rotary engine for one-more year, but at the end of 1992 this IMSA programme also came to an end.

However, it wasn’t just success at Le Mans that marked Mazda out in the 1980s and 1990s, with rallying changing to Group A regulations, Mazda took on contenders from Lancia, Toyota and Ford with the Mazda 323 AWD. However, in spite of producing 250bhp, the 323’s 1.6-litre engine didn’t have the power of the bigger 2.0-litre units in rival cars, fortunatly its dimunative size and nimble handling played to its advantage, particualry on ice rallies. Something Timo Salonen highlighted by winning the 1987 Swedish rally, while in 1989 Ingvar Carlsson repeated that feat when he took the win in Sweden. In what proved to be the Mazda’s most succesfull season, he added another win with victory in the New Zealand Rally, while local driver Rod Millen was second in another 323. At season end Mazda celebrated third place in the World Rally Constructors championship and continued rallying the next-generation 323 into the 1990s, before in 1991 the company withdrew from the World Rally Championship.

In the hands of private teams and drivers, the Mazda 323 went on to be a very popular and succesfull car in Group N rallying. Today, the Mazda 323 remains a somewhat forgotten star in Mazda’s all-wheel drive heritage, but it was the launch of the Mazda MX-5 in 1991 that really made Mazda a mainstay of amateur racing across the globe. Raced by owners in one-make cups, endurance races and amateur competition of all varieties – the MX-5’s driver engagement meant every generation found its way onto the race track, with the third-generation even taking on the Nurburgring 24 Hours in 2014, while in 2012 Mazda UK built the bespoke MX-5 GT4 car and competed in the British GT Championship. Today, the fourth-generation MX-5 competes in the Super Taikyu Endurance Series in Japan, while the MX-5 Global Cup is one of the most popular and most competitive one-make cup series in the United States.

While Mazda Corporation stepped away from global motorsport at the start of the nineties, success continued in the United States and today Mazda Motorsports North America continues to compete at the highest level with a two-car factory supported effort in the 2020 IMSA Sportscar Championship with the stunning Mazda RT24-P prototype. With British drivers Oliver Jarvis and Harry Tincknell on the driving squad the team heads into the 10-hour Petit Le Mans at Road Atlanta this weekend.

Even better, when it comes to racing on road course circuits in the USA, more private competitors race a Mazda or a Mazda powered car than any other brand and across the world from Mexico to Australia, from Europe to North America, and at home in Japan, Mazdas are chosen by drivers and teams to race and rally – highlighting the driver’s car ethos at the heart of every Mazda.